Archaeology

Before approximately 3000 BC, when Florida’s sea level was 100 meters (over 300 feet) lower than today, much of the present continental shelf was exposed. Although fewer than 100 prehistoric sites have been discovered scattered throughout Florida, many more likely remain submerged deep in the ocean and far from shore, where the coastline used to be.

When climate changes created the variety of environmental habitats in South Florida today, groups built permanent villages, which did not change much over hundreds of years, but tools and pottery styles did. They assist archaeologists in locating and dating prehistoric sites, although most sites have been discovered accidentally and by laypeople, such as the Riddle effigy.

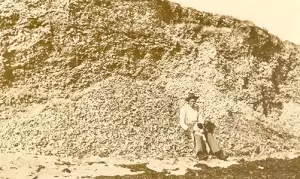

Signs of occupation by prehistoric populations include sand earthworks and burial mounds, shell mounds, black earth and shell middens, and embankments. Mounds had various purposes: a memorial or landmark over a burial place, a ceremonial or religious place, a refuse heap, or an embankment built as a dam or a causeway for travel.

Refuse mounds, or kitchen middens, are primarily sand, black earth, or shells, depending on their locations. Middens of discarded oyster shells are common near the coast. Inland, black earth middens contain dark brown or black soil stained by decayed organic material, such as the remains of animals and marine life. Remnants of ceramics and tools, and objects of art may be included, when made of materials that do not break down in the soil. According to archaeologist Randolph J. Widmer, the kitchen middens of prehistoric people prove that “second only to what is now known as southern France—southern Florida was the most populated area on earth.”

Signs of occupation by prehistoric populations include sand earthworks and burial mounds, shell mounds, black earth and shell middens, and embankments. Mounds had various purposes: a memorial or landmark over a burial place, a ceremonial or religious place, a refuse heap, or an embankment built as a dam or a causeway for travel.

Refuse mounds, or kitchen middens, are primarily sand, black earth, or shells, depending on their locations. Middens of discarded oyster shells are common near the coast. Inland, black earth middens contain dark brown or black soil stained by decayed organic material, such as the remains of animals and marine life. Remnants of ceramics and tools, and objects of art may be included, when made of materials that do not break down in the soil. According to archaeologist Randolph J. Widmer, the kitchen middens of prehistoric people prove that “second only to what is now known as southern France—southern Florida was the most populated area on earth.”

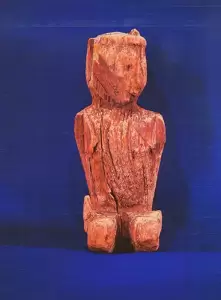

Riddle Effigy

The unique wet environment of the Everglades created oxygen-free soil that acted as an excellent preservative for wood artifacts created by Florida’s early population. In 1928 engineer Karl Riddle discovered such an artifact, a small statue carved from cypress, while working on road construction near Pahokee, on the east side of Lake Okeechobee.

The human effigy is one of few found in south Florida, and is believed to represent a shaman, leader, or ancestor. The Calusa were expert woodworkers, who may have taught their craft to the people of the Belle Glade culture. Woodworking tools that may have been used to create the figure include those found at Belle Glade, made of shark teeth attached to a wood or bone handle. Early south Floridians also commonly used barracuda jaws and teeth, shells, and stingray spines. A woodcarving of a human figure recovered at Belle Glade, although in a standing position, has a hair knot at the back of the head similar to the Riddle effigy.