Central County: Westward Expansion

A new era of prosperity followed World War II. In West Palm Beach, property values rose from $72 million in 1949 to $147.5 million in 1962. The city’s population reached 43,162 in 1950 and rose 30% more by 1960. Although new residents arrived daily, West Palm Beach had limited growing room and a primitive sewer system. Henry Flagler’s estate owned the water treatment plant and the land west of the city. In 1955 the city passed an $18 million bond issue, which it used to purchase the water plant and 20 square miles of wetlands (now Grassy Waters Preserve) from Flagler Water Systems and 17,000 acres from Flagler’s Model Land Company, and upgrade the sewer system.

A new era of prosperity followed World War II. In West Palm Beach, property values rose from $72 million in 1949 to $147.5 million in 1962. The city’s population reached 43,162 in 1950 and rose 30% more by 1960. Although new residents arrived daily, West Palm Beach had limited growing room and a primitive sewer system. Henry Flagler’s estate owned the water treatment plant and the land west of the city. In 1955 the city passed an $18 million bond issue, which it used to purchase the water plant and 20 square miles of wetlands (now Grassy Waters Preserve) from Flagler Water Systems and 17,000 acres from Flagler’s Model Land Company, and upgrade the sewer system.

Two years later the City of West Palm Beach sold 5,500 acres of its westward expansion area for $4.35 million to a partnership. Because of financial difficulties, all the partners withdrew except one: Louis R. Perini, Sr., president of Perini Corporation of Massachusetts, which had been founded by his immigrant father, Bonfiglio Perini. Perini’s development company spent millions of dollars making the expansion area buildable. Gee and Jensen Engineers added 30 million cubic yards of fill to transform the swamp into dry land. Attorney Frederick C. “Ted” Prior, who handled legal work for Perini in the ‘70s, recalled: “Where the Palm Beach Mall and all that [is], that was where we used to hunt and fish as little boys back in the ‘30s.”

The city required Perini to start with housing for African Americans, partly in reaction to a 1951 University of Miami study that characterized the black neighborhood of West Palm Beach as a congested slum. On 500 acres west of the Northwest and Pleasant City communities, between Lake Mangonia and Clear Lake, Perini added moderate-income Roosevelt Estates. West Palm Beach maintained segregation until federal Civil Rights legislation prohibited it in the 1960s. Strong leadership in the African American community and the development of Roosevelt Estates minimized racial conflict during this period.

Perini extended 12th Street through Roosevelt Estates, renamed it Palm Beach Lakes Boulevard, and turned it southwest to meet Okeechobee Boulevard. In 1966 Perini completed the first section of Interstate 95 in Palm Beach County, 3.6 miles from Okeechobee Boulevard to 45th Street. These two roads greatly changed West Palm Beach.

Perini Land and Development made the expansion area buildable, and then sold much of it back to the city—which built the Municipal Stadium (1963) and the West Palm Beach Auditorium (1967)—and to other developers, who added the Palm Beach Mall (1967), and other landmarks on Palm Beach Lakes Boulevard.

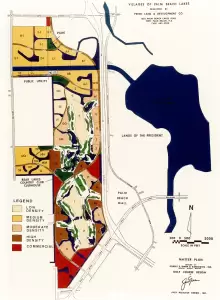

Villages of Palm Beach Lake development by Perini Land and Development Co. Golf Course design by Jack Nicklaus, Inc.

Although Louis Perini, Sr. died in 1972, Perini Land and Development continued its effect on West Palm Beach during the 1970s and ‘80s with residential and mixed-use projects of its own. The Land of the Presidents was among the area’s first country club developments, on 242 acres east of Congress Avenue and I-95 and north of Palm Beach Lakes Boulevard. West of I-95, the 1,400-acre Villages of Palm Beach Lakes included 4,000 residences as well as offices, retail shops, and golf courses designed by legends, such as Jack Nicklaus. As the population and economic base continued to be shifted to the suburbs, the downtown and the older residential sections of the city began a slow decline.

The Downtown Exodus

George Greenberg (1915-2007), known as the “Mayor of Clematis Street,” took his family’s Pioneer Linens through half a century of downtown changes, beginning in 1957: “It was a very thriving area at that time. We had a J.C. Penney’s store, we had a Montgomery Ward’s, we had Sears, and the first sign of erosion was when Sears built a store out on South Dixie [Highway].” Dixie Highway was impacted along with downtown by development west of the city. As new hotels were erected near the Interstate 95 exits, motels along Dixie Highway rapidly went out of business. Sears moved again to the Palm Beach Mall, as did the anchor stores from downtown, including F. W. Woolworth’s, J. C. Penney’s, and Burdines, which had been there for almost 40 years.

Greenberg said, “The retail exodus took several years, but the mall affected it immediately.” In 1967 Greenberg helped found the Downtown Development Authority to formulate long-range plans for its facilities, and especially to retain and attract businesses:

The need seemed to be that to really turn things around downtown, we needed to raise some money. So I was able to prevail upon five or six of our downtown principals. … I had heard about this development authority being authorized in the state of Florida, so we went around and got over 50% of the property owners in the downtown to agree to pay a one-mil tax on ourselves, and we developed the DDA. We got the head of First Federal [Savings and Loan], George Preston at that time, to become the chairman.

George Greenberg

Retail Highlights

Urban expansion brought constant change to the retail environment that continues today. Small family-owned businesses in downtown areas gave way to shopping centers and finally to enclosed malls filled with upscale national tenants. Here are some of the highlights of retail development during the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s:

1959: The first Publix in Palm Beach County opened at Lantana Shopping Center on Lantana Road, now an exit on I-95. In 2002 the store expanded to 61,000 square feet, half of the renovated center.

1959: The county’s first shopping center, Palm Coast Plaza, opened on Dixie Highway in West Palm Beach, just north of the Lake Worth city limits.

1967: The million square-foot Palm Beach Mall opened on Palm Beach Lakes Boulevard in West Palm Beach.

1971: The Twin City Mall, North County’s first, opened at US 1 and Northlake Boulevard, with half on each side of the Lake Park-North Palm Beach city limits.