The Civil Rights Era in Palm Beach County

The 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s were volatile years in the United States, while African Americans fought for equal rights and others resisted, particularly in the traditional South. Palm Beach County was diverse in its attitudes; national or state events found varying reactions here. In the transitional climate, leaders and role models, both black and white, came forward, and there were many “firsts”; a sampling is presented chronologically:

The first female mayor of Delray Beach, Catherine Elizabeth Link Strong, was chosen by the City Commission in 1954. That year she assisted the black community with their requests for a designated black beach. As a commissioner in 1956, during differences over use of the municipal pool and beaches by blacks, Strong denied remarks attributed to her in Jet magazine, written by “outsiders who do not really understand the background of Delray’s problems.” Weeks earlier, Strong had voted against a resolution that would have redefined the city’s boundaries to exclude the “Negro Area” that a biracial committee had agreed on in 1935.

The West Palm Beach City Commission voted in 1962 not to change the provision of the 1916 deed to Woodlawn Cemetery that restricted its use to whites. Four years later, attorney William M. Holland, local NAACP president Louise E. Buie, and two other African Americans paid deposits on plots at Woodlawn. The commission voted 4:1 to integrate Woodlawn. Holland and Buie were buried there in 2002 and 2003, respectively.

A black middle class formed in Palm Beach County in the 1960s, when big industry brought black professionals from other states and trained locals for similar positions. The U.S. Census Bureau reported that the number of blacks in the county with purchasing power of at least $10,000 increased three-fold from 1960 to 1970. In West Palm Beach, Roosevelt Estates and other middle-class black subdivisions sprang up around Clear Lake and Lake Mangonia; Progressive Park in Belle Glade was a similar neighborhood. Some African Americans, including attorney Thomas James “T.J.” Cunningham, chose to live in white neighborhoods when they could afford to, with little apparent trouble.

The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, part of President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” established social programs such as Job Corps and Head Start. Local liaisons included Maude Ford Lee, F. Malcolm Cunningham, Sr., Louise E. Buie, and Charlie Lovett Ellington, who became the first black supervisor of special education for the northern part of Palm Beach County; she taught for 32 years in Palm Beach County schools.

Ozie Franklin Youngblood (1906-1992) in 1968 became the first black member of the Delray Beach City Council. He wrote a 22-page book, A Man of the Twentieth Century, about his early struggles as a community activist.

In 1974 the First Prudential Bank of Palm Beach County opened, later known as Palm Beach Lakes Bank and Southcoast Bank, and the first and only commercial bank for minorities in the county. Circuit Court Judge Edward Rodgers (1927-2018) was chairman of the board of directors.

Also in 1974, the Urban League, which helps African Americans and other minorities achieve economic independence and enjoy their civil rights, opened its fifth Florida affiliate in Palm Beach County, with Percy H. Lee as president. Co-founders included Harriette Sangerman Glasner and Charlie Lovett Ellington.

Alcee L. Hastings (1936-2021) was appointed Circuit Court judge in 1977 and served until 1979, when President Jimmy Carter nominated Hastings, the first black man to hold the U. S. District Court, Southern District of Florida.

Cunningham and Cunningham

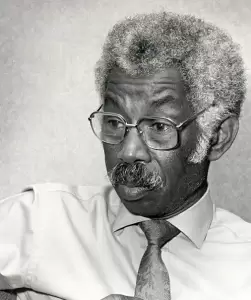

Frank Malcolm Cunningham, Sr.(1927-1978) and Thomas James “T.J.” Cunningham, Sr. (1930- ) were born into a farming family in Plant City, Florida. Both brothers earned a bachelor’s degree from Florida A&M University and a law degree from Howard University; no Florida law school was then open to blacks. Malcolm opened a practice on Rosemary Avenue, West Palm Beach, where T. J. joined him in 1960; the law office of William M. Holland and I.C. Smith was across the street.

In 1962 Malcolm Cunningham became the first black person voted into public office in Florida since Reconstruction, when he was elected to the Riviera Beach Town Council with 18% of the white vote; six years earlier, someone burned a cross outside the town’s polling place for blacks. After three terms on the council, Cunningham left as its chairman to run, unsuccessfully, for the Florida legislature.

Malcolm and T.J. Cunningham were actively involved in integrating Florida’s Turnpike facilities, Palm Beach County’s school system, and West Palm Beach’s golf courses. In 1973 the brothers helped found First Prudential Bank in West Palm Beach, the first minority-owned commercial bank in the state. Their firm, Cunningham & Cunningham, remains one of Florida’s oldest black law practices.

African American Legal Groups

The Florida Chapter National Bar Association (now the Virgil Hawkins Florida Chapter National Bar Association) was founded in the 1950s by members of the Chi Epsilon legal fraternity, including F. Malcolm Cunningham Sr., T.J. Cunningham, Sr., William M. Holland, and Isaiah Courtney “I.C.” Smith of West Palm Beach. They declared their mission as ensuring access to the justice system, increasing economic parity, and educating the black community on the need for empowerment and self-determination. In the 1960s, black female lawyers were invited to join, and the organization became a state affiliate chapter of the National Bar Association.

A group of black West Palm Beach attorneys began meeting informally in the 1970s, including the Hon. Edward Rodgers, the Hon. Catherine Brunson, William M. Holland, F. Malcolm Cunningham, Sr., and T.J. Cunningham, Sr. After Malcolm Cunningham died in 1978, the group formed the F. Malcolm Cunningham, Sr. Bar Association to support black attorneys and “redress the social ills that impeded blacks’ social, economic, and political progress.”