North County: MacArthur Country

A bridge over the Intracoastal Waterway at Monet Road (now RCA Boulevard) was destroyed in the 1947 hurricane. After Donald Ross Road was built in 1956, a bridge was added to it. In the early 1960s, the State of Florida crossed the Intracoastal at PGA Boulevard (S.R. 786) and expanded the waterway to 125 feet wide and 10 feet deep.

John Maheu, whose family settled in Prosperity Farms in 1920, farmed along Prosperity Farms Road in today’s Palm Beach Gardens until the late 1950s. East of the road, he dredged finger canals from the Intracoastal Waterway and subdivided his land as Maheu Estates. Maheu sold his land on the west side of the road to millionaire John Donald MacArthur (1897-1978), who formed the Cabana Colony subdivision from part of it in 1960; Cabana Colony was nearly built out by 1968.

In 1954 MacArthur paid $5.5 million for 2,600 acres owned by the estate of Sir Harry Oakes as Tesdem Company, Inc. The land, previously owned by Harry Seymour Kelsey, included Lake Park and what would become the original Palm Beach Gardens and North Palm Beach.

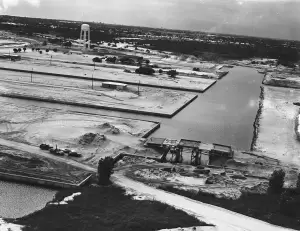

Contractors Bob and Dick Ross quietly developed North Palm Beach between US 1 and Prosperity Farms Road, using extensive dredging to maximize the amount of waterfront property. Lake Park West Road was extended from US 1 to Old Dixie Highway and renamed Northlake Boulevard, the town’s commercial east-west road. Lighthouse Drive was widened between US 1 and Old Dixie Highway through the residential area.

Incorporated in 1956, North Palm Beach was named the year’s Best Planned Community in the U.S. by the National Association of Homebuilders. The village became the bedroom community for the professionals who came to work at Pratt and Whitney, which opened west of town in 1958.

In 1959 MacArthur incorporated 4,000 of his acres as the City of Palm Beach Gardens. His first name choice, Palm City, was refused by the State of Florida as too similar to the Town of Palm Beach. The final name matched MacArthur’s plans for a garden-themed community, with winding streets named for the flowers and trees to be found throughout.

Palm Beach Gardens grew to 1,800 residents in just over a year. Arthur Rutenberg, who built homes on the east and west coasts of Florida from 1953 to 1969, constructed many of the first houses in both Palm Beach Gardens and North Palm Beach. By 1970 Palm Beach Gardens had a population of over 6,000 people; slow but steady growth throughout the ‘70s doubled the number of residents by 1980.

Banyan Mac

As a developer, John D. MacArthur was often accused of destroying the environment, but he argued, “I built Palm Beach Gardens without knocking one tree down, [and] I moved the biggest tree ever moved in Florida.” The 60-foot tree, a banyan, weighed 75 tons and had a limb spread of 125 feet. It took six months to prepare the tree for the five-mile trip from its home, where its roots were damaging the street and it was at risk to be cut down. In 1961 MacArthur had the banyan moved to Garden Boulevard (now MacArthur Boulevard), at the entrance to his new city.

Two cranes lifted the tree onto two cargo trailers. MacArthur remained with the tree during its journey. Despite extensive planning, problems along the route disrupted south Florida’s telegraph and telephone communications and operations of the Florida East Coast Railway. The tree’s planting was blessed by a priest and filmed by a television crew. The process cost $30,000 and 1,008 hours of manpower. A year later, MacArthur moved a smaller, 40-ton banyan tree next to the first one. In 2007 Alexandre Renoir, great-grandson of artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir, presented a painting of the banyan trees to the City of Palm Beach Gardens.

Banyan Mac moved almost 200 trees, including a 60-foot Norfolk pine that he replanted at the Colonnades Hotel on Singer Island, which he bought from the estate of A. O. Edwards, founder of Palm Beach Shores, and used as both home and office. MacArthur saved four more banyans, floating them on a barge from West Palm Beach.

MacArthur and the PGA

[Jerome B.] Jerry” Kelly, who was one of MacArthur’s right arms, … induced the PGA of America to move its national headquarters to this newly created city with no people in it, named Palm Beach Gardens, if MacArthur would build them—and he did—two 18-hole golf courses. And he loaned them the money to finance a clubhouse.

Frederick C. Prior

E. Llwyd Ecclestone, Jr. (1936-) and the PGA

He was independent, did what he wanted to do. He also, like my dad, knew land and knew location and bought outstanding values of land. …. The guy was a genius. Of course, he was a little eccentric, but if you treated him equal—you don't go to him and say, “Hey, you've got more money than I do, you've got to give me a break.” You go in and deal as if you're absolutely an equal with him, make sure you pay him everything you agreed to pay him, you do exactly what you say you're going to do, and he was a really good person to do business with.

E. Llwyd Ecclestone, Jr.