School Desegregation

William Meredith “Bill” Holland, Sr. (1922–2002), in 1951 the first black attorney in West Palm Beach, was joined by Isaiah Courtney “I.C.” Smith (1921- ) in 1954; they had met en route to Florida A&M College in 1941. Three months before Smith arrived, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed a 58-year-old ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, arguing that racially segregated educational facilities were “inherently unequal,” but supplying no timetable for school desegregation. The Palm Beach Post carried no local reaction, although Acting Governor Charley E. Johns was in West Palm Beach when Brown was announced. A second Supreme Court decision in 1955 dubbed Brown II required “a reasonable and prompt start toward full compliance with the 1954 ruling.”

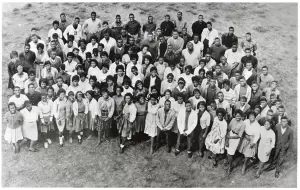

Palm Beach County’s black community took pride in the high standards of their all-black schools, where respect, discipline, and self-esteem were as important as academics. School, church, and home were closely related in local black communities, and black teachers often knew their students’ families.

Black schools were handicapped, however, by inferior facilities and materials. Bill Holland recalled that when he came to West Palm Beach, “Even the textbooks for white and ‘Negro’ students were kept in different warehouses. … All of our supplies were handed down from white schools.” When Palm Beach County “all but equalized the facilities,” according to educator C. Spencer Pompey, many blacks became less interested in integration. Their goal was not to share classrooms with white students, but to share their level of funding and materials.

When Bill Holland’s son reached school age in 1956, Holland and Smith pushed officials into a test case. After the county denied William Jr. entrance to all-white Northboro Elementary for two years, Holland and Smith filed a class-action suit and returned to the courts again and again. To comply with one ruling, in 1961 Palm Beach County offered a plan that resulted in four black students transferring to white high schools: Yvonne Lee, Theresa Jakes, Johnnie Green, and Iris Hunter. By 1965, of the county’s 15,000 minority students, 137 attended predominantly white schools.

In 1966 the U.S. Commissioner of Education used the recent Civil Rights Act to motivate school districts to comply with Brown or lose their federal funding; he also ordered the closing of “inadequate schools maintained for Negroes.” Although Palm Beach County pledged compliance, in 1967 only Jupiter High School had achieved full desegregation and all-black schools remained open.

Several local black organizations worked toward desegregation, including the Imperial Men’s Club of Riviera Beach and the United Front, which organized boycotts in 1969. A biracial group of educators, ministers, and business people formed the United Guidance Council (UGC). At a meeting with school officials, UGC’s white co-chair Leo B. Schwack observed, “This is probably a new era in this community’s lifetime. Could you look back at any time in the past when a group such as this could sit down with a so-called ‘power structure,’ air your thoughts … get responses? Everything we have gone through has not been in vain.” The dialogue led to progress; in 1970 only one of 13 former all-black county schools remained above 90% black.

At the 1969 UGC meeting, Deputy School Superintendent Russell Below described the inaction that had delayed desegregation: “Most plans have been developed to circumvent integration nationwide and … I am one of the educators who hasn’t had guts enough to stand up to the man on the street and say it has got to go this way for good education programs; but instead we stood aside and let [the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare] become God.”

Some members of the black community protested the years of delays; others were frustrated or angry over their loss of identity in predominantly white schools. White parents were also angry when their children were bused to black neighborhoods. During the first year of desegregation, 3,300 white students left public school. Some reactions were less passive: a stick of dynamite on a school bus and police in riot gear in Riviera Beach, fires at Twin Lakes High in West Palm Beach, students cut with razors at Boca Raton High, and fistfights and bomb threats at Atlantic High School in Delray Beach.

On July 9, 1973, a U.S. District Court judge issued the final ruling in the Holland case and declared Palm Beach County School District to be officially integrated. The Office for Civil Rights, however, monitored the county’s schools until 1999.

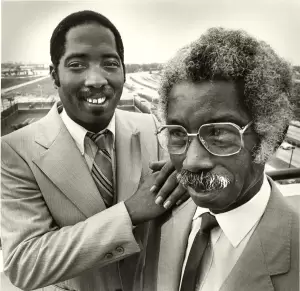

Daniel W. Hendrix

When all-black Roosevelt Junior College merged with Palm Beach Junior College (PBJC) in 1965, Daniel W. Hendrix, a math instructor, was one of six Roosevelt staff members to move to PBJC. In 1970 Hendrix became the first African American elected to the Palm Beach County School Board, and to any countywide position.

Other Leaders

Leo B. Schwack (1917–2005): Leo Schwack moved to West Palm Beach in 1945, where he was one of the founders and president of Temple Beth El. In 1960 he established The Palm Beach Chemical Company. Schwack devoted countless hours to the Parent-Teachers Association (PTA); in 1968 he received life membership in the National Congress of Parents and Teacher. The Classroom Teachers Association presented Schwack with its School Bell Award for his help in resolving the teachers’ salary crisis of 1967.

Leo Schwack was appointed by Gov. Bob Graham to the Governor’s Alliance for Employment of Disabled Citizens and re-appointed by Govs. Martinez and Chiles. In 1987 he was recognized with the Theodore Norley Award for Community Service for his outstanding work for the disadvantaged citizens of Palm Beach County, including serving as chairman of the Urban League.

C. Spencer Pompey (1915-2001): C. Spencer Pompey was a founder and president of the Palm Beach County Teachers Association for black teachers in the 1940s. He was an educator for 40 years, teaching social studies at all-black Carver High School in Delray Beach before becoming its principal. As a football coach, Pompey led the Carver Eagles to unbeaten seasons in 1949, 1950, 1961, 1962, and 1963. The games were popular with both blacks and whites, although they sat on different sides of the field.

Spencer Pompey fought to open the city’s whites-only beach to blacks in the 1950s and to start recreation programs for Delray’s youth. He authored a book about the process of desegregation in Palm Beach County, More Rivers to Cross, which his widow, Hattie Ruth Pompey, published after his death.