The Grand Hotels: The Royal Poinciana

In 1893 construction began on the Royal Poinciana Hotel in Palm Beach, after Commodore Charles J. Clarke had purchased the Cocoanut Grove House from Elisha Dimick. Clarke’s guests were forced to find other accommodations when he leased the entire hotel to Flagler for a hundred of his upper-level employees. Six months later the Cocoanut Grove House burned to the ground, and the employees were also seeking shelter. One thousand workers helped to build the Royal Poinciana, using 1,400 kegs of nails, 360,000 shingles, 500,000 bricks, 500,000 feet of lumber, 2,400 gallons of paint, 4,000 barrels of lime, 1,200 windows, and 1,800 doors, among other materials.

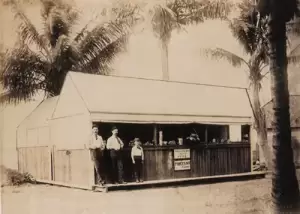

About 1,400 employees operated the hotel’s own bakeshop, ice cream shop, post office, incinerator, and electric power plant (added in 1901). Burkhardt Brothers sold fruit and oysters on the hotel grounds, and other shops operated in front of the hotel, such as Anthony Brothers which sold menswear.

The train to Palm Beach carried only passengers, who went straight to the island. Their considerable luggage, however, was left at the depot in West Palm Beach to be delivered to their hotel room by a crew of four baggage handlers, including Victor McCarthy, who talked in 1962 about his ten years transferring bags to the Royal Poinciana:

All the baggage, we’d transfer it from one wing to another just by wagons [pulled] by men! One family probably had, I’d estimate, ten to fifteen trunks. I transferred trunks from one room to the other, and you had to have the guard to go along with you, because the building was so large that you’d never find your way out, and sometimes he’d get shook up in there. No, no elevators!

Victor McCarthy

Although he only had an eighth grade education, Henry Flagler felt a responsibility as a social leader. While he did not follow his minister-father’s faith, he thought churches were important to developing a community. Flagler donated a vacant lot at the south end of the hotel and built the Little Church, today’s Royal Poinciana Chapel, and arranged for its financial security during his lifetime. To accommodate all his Christian guests, Flagler made the church non-denominational.

The Fanny Dugan Line

Part of the activity inspired by Flagler’s arrival in Palm Beach was the pioneers’ improvement of their homesteads. Joseph Borman, who would become town marshal and tax collector of Palm Beach, performed day labor for the residents when he arrived in December 1894:

“Captain” [Elisha N.] Dimick and George Lainhart lived side by each and they was fillin’ in the swampy land in back of their places from the beach hammock with a little dinky railroad that we named the “Fanny Dugan Line”; me and my pal [Manfred B. Monroe] named it that. Just from the lakeshore not quite to the ocean. Hauling sand and fillin’ in, y’know. They had six dump cars. They had men shoveling sand. So it was ten cents a yard, I think. Every once in a while they’d move the track a little bit. It was all laboring work, a dollar and a quarter a day. We done so good, he paid us eight bucks a week apiece.