Early Tribes: Seminoles and Miccosukees

Florida has been home to the Seminole Indians since the mid-1700s. When Florida’s original population of Native Americans decreased, groups of Lower and Upper Creeks, (classified by which waterway they lived near), also known as Muscogees, moved into Spanish Florida. They came from Alabama and Georgia seeking their own land, and Florida had plenty available. Eventually, there were two dominant tribes, the Miccosukees and the Seminoles, separated by their languages. The Miccosukees’ language descended from the Lower Creeks, while the Seminoles’ language came from the Upper Creeks. The name “Seminole” could have two meanings. From the Creek phrase phegee ishti semoli, Seminole means “wild men.” From the Spanish cimarrone, Seminole means “runaway.”

The Seminoles fought three wars against the Americans. The First Seminole War started in 1818 because Seminoles in Spanish Florida made raids across the border into the United States. General Andrew Jackson led American forces into Florida, captured several Spanish towns, and executed two British citizens that he believed were spies. The Americans were also upset that slaves from Georgia and Alabama were escaping to Florida to live with Seminoles, with whom they shared a goal: freedom from control by white men.

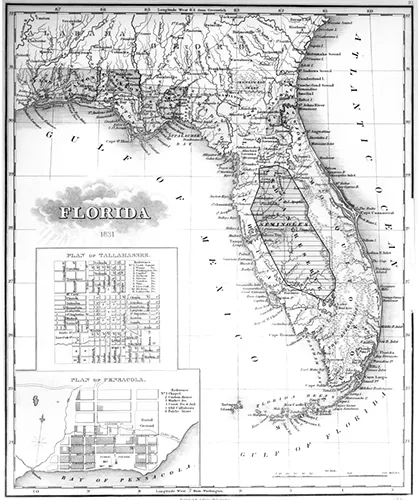

In the 1820s, after Florida became part of the United States, American settlers often clashed with Seminoles over land. In the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek, the Seminoles agreed to give up their land and move south to 4,000,000 acres of land in central Florida. The Seminoles also agreed to return runaway slaves.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed for the whole United States by President Andrew Jackson, the former army general. The act required all Native Americans to move to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), west of the Mississippi River. Some Seminoles did not want to leave their homes, but they did agree to send a group to see the place where they were to relocate. During their visit, the group was persuaded to move there, but after they returned to Florida, many of the chiefs said they had been forced to sign the agreement. The Seminoles refused to leave Florida, leading to the Second Seminole War from 1835 to 1842.

Osceola emerged as a Seminole leader and was one of those who refused to leave his home. In December 1835 he led a small group of warriors on an attack, killing a government agent who had earlier thrown him in jail. On the same day, a large group of Seminoles attacked Major Francis L. Dade and over 100 soldiers on their way to Fort King (now Ocala, Florida). Only three of Dade’s men survived. Osceola was eventually captured, and died in a South Carolina prison in 1838.

The war raged on until 1842, when Colonel William Jenkins Worth (for whom Lake Worth was named) declared it over. Most of the Seminoles were either killed or captured and sent west to the Indian Territory. A few hundred others retreated to the Everglades in south Florida. The Second Seminole War was the most costly of all Native American wars in terms of lives lost and money spent.Once there was peace again, more whites felt confident enough to establish homes, farms, and businesses in Florida without fear of Seminole attacks. The territory’s white population soon topped 60,000, which was the number of people needed to become a state. On March 3, 1845, Florida entered the Union as the 27th state.

Ten years later, the Third Seminole War began. An American surveying team caused this war by destroying Chief Billy Bowlegs’ banana trees, in his garden deep in Big Cypress Swamp. When Bowlegs confronted the men, they not only refused to pay for the damage, but also refused to apologize.

The following day, the Seminoles attacked them, killing or wounding the entire surveying team. This led to another war, which lasted until 1858, when Bowlegs and his band were forced to surrender and were moved to the Indian Territory. The remainder of the Seminoles moved deeper into the southern Everglades to avoid white control.

The Seminoles and Miccosukees in Florida today are descendants of those who refused to give in or to sign a treaty to move to the Indian Territory.