Getting Around: Houses of Refuge

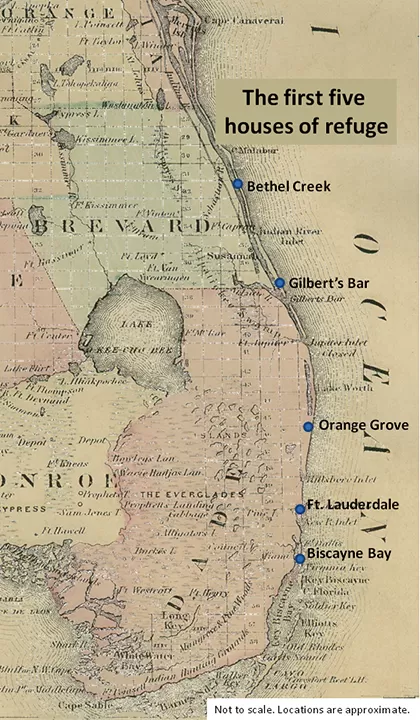

Houses of Refuge

- Biscayne Bay House of Refuge No. 5: (1876-1909) about ten miles south of New River Inlet

- Gilbert's Bar (St. Lucie Rocks) House of Refuge No. 2: (1876-1914) on present Hutchinson Island in Martin County

- Orange Grove House of Refuge No. 3: (1876-1896) 15 miles north of Hillsboro Inlet, near the present city of Delray Beach

- New River (Fort Lauderdale) House of Refuge No. 4: (1876-1909) four miles north of New River Inlet

- Biscayne Bay House of Refuge No. 5: (1876-1909) about ten miles south of New River Inlet

Ten years later, four more houses were built north to St. Augustine: Smith’s Creek (Bulow), Mosquito Lagoon, Chester Shoal, and Cape Malabar, which closed after only four years of operations. In 1896 the Orange Grove House of Refuge closed. The rest continued to fill a need into the 20th century, although only one building remains; Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge Museum is operated by the Martin County Historical Society.

Orange Grove House of Refuge No. 3

The only house of refuge built in Palm Beach County was located about a quarter mile north of a sour orange grove, east of the ocean ridge, near the present City of Delray Beach. The two-story wood frame building was designed for hot summers, with a wraparound porch and low sloping roof.

On the first floor were four large rooms, the residence of the keeper of the house. The second floor, one open room, had large windows at each end for cross-ventilation. This room was kept in constant readiness with cots and provisions for 20 guests for ten days. Bedding, clothing, medicine, books, and dried and salted food were on hand, which were carefully maintained by the keeper. A separate boathouse held two lifeboats, signaling flares, and other lifesaving equipment.

Besides maintenance, the keepers’ duties included logging the weather three times per day and any passing ships or people. After a storm, they were to search the area for anyone in need. In the early 1880s the keepers also preserved unusual specimens of marinelife for the Smithsonian Institution. Most keepers sought extra income through work such as farming, boatbuilding, or beekeeping.

The Lifesaving Service preferred keepers with families for the extra help and company they could provide in the lonely wilderness. In the early years, sailboats were common on the ocean and inland waterway, and they often stopped at the houses. The superintendent made quarterly inspections, when he paid the keeper, and Seminole Indians called to trade meat, as they did at other south Florida settlements.

Although the houses generally proved to be an unhealthy environment, Hannibal Pierce’s wife, Margretta Moore Pierce, gave birth to Lillie Elder there, the first white girl born between Delray Beach and Biscayne Bay. Margretta missed her Hypoluxo Island home and returned with the children after 13 months; Hannibal remained until Steve Andrews replaced him in January 1878. The family also served at the Biscayne Bay House of Refuge No. 5 in 1883 and 1884, perhaps attracted by the increase in annual salary, from $400 to $500.

The second and last keeper of Orange Grove House of Refuge No. 3, Steve Andrews, had recently come to Biscayne Bay from England; he married Annie Hubel of Michigan a few years into his service. Andrews raised hogs and chickens, and took pride in his garden.

A Neighborly Visit

One day at Orange Grove House of Refuge No. 3, Margretta Pierce was alone with her two children—Lillie, an infant, and Charles, 12—when they had a visitor, as Lillie later related:

[I]n walks a big Indian, had a big knife in his hand. My mother was wearing a very pretty bright red flannel jacket she’d made off of some of that wreck stuff, off the Victor wreck, probably. He laid his knife on her arm [and] he says, “Got any more like ‘em?” She said, “No.” So he didn’t bother anymore, he went off. My brother, though, was afraid that Indian was gonna give trouble, so he was edging into the dining room to get where the shotgun was. He was gonna shoot that Indian, but he didn’t get the chance. … Charlie went up on the roof and watched him go, way off through the underbrush and through the scrub till he was sure he was gone. But it frightened my mother considerably.

From 1888 to 1892, Annie Andrews was postmistress of the Zion Post Office at House of Refuge No. 3. In 1894 Congressman William Seelye Linton led a group from Michigan to south Florida to establish a new community. In West Palm Beach they heard of land for sale near House of Refuge No. 3, which they reached by barge, down the inland waterway. Linton bought, platted, and officially recorded a new settlement, the Town of Linton. The following year, when he brought his first purchasers from Michigan, they stayed at House of Refuge No. 3 while clearing land and erecting temporary shelters.

Fast Friends

In April 1890, while visiting on Lake Worth, Emma and Annie Gilpin and friends accompanied George Potter on his sharpie sailboat, the Heron, when he took the tax collector to Miami. On the trip south, the party met mail carriers, house of refuge keepers, and sometimes stormy weather. Gilpin wrote of the return trip along the coast:

When we pass O’Neill’s [New River House of Refuge No. 4], I spy a light in his window and the moonlight on the roof; Capt. P. blows a blast on his conch shell, and immediately we get the response of his brightening light, and soon after a blow from his horn, and a whine from his dog, Wusley. The musical greeting is kept up on both sides until we drop the House altogether – a cheery good-bye from a good friend.