Getting Around: Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse

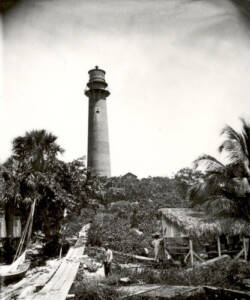

The oldest building in Palm Beach County, the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse, has helped ships steer clear of dangerous ocean shoals and reefs since 1860. Construction of the 108-foot-tall tower, built on a 48-foot-high mound, took six months and cost $60,000. At times the beam of its French-made Fresnel lens could be seen almost 20 miles into the Bahamas Channel on the other side of the Gulf Stream.

When the project crew departed in May 1860, two men were named to stay on as caretakers until the first lighthouse keeper arrived. In the U. S. Census dated June 20, 1860, however, Charles and William Patterson are listed with the occupation of “sailors keeping light house.” Further, the census conflicts with Lighthouse Service records, which show the first head keeper, Thomas Twiner, and his assistant, Peter Pomar, took over on June 12, 1860; they were replaced seven months later.

Lighthouse duty was lonely most places, and especially so at Jupiter. The first men, without families, were the only non-Indian residents in a vast wilderness, and settlers were not expected any time soon. Until 1884, the lighthouse was part of the 9,100-acre Fort Jupiter military reservation created in 1855. Delivery of supplies was infrequent and especially difficult, coming by river barge from the Indian River Inlet or left on the beach at high tide.

Florida seceded from the United States of America on January 10, 1861, and joined the Confederate States of America; three months later, the Civil War began. As in other parts of the country, the people scattered around southeast Florida did not always share the view of their neighbors. José Francisco “Joe” Papy, the second head keeper of the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse, was loyal to the Union. His two assistants were Confederate sympathizers: Francis A. Ivey, a veteran of the Third Seminole War, and Augustus Oswald Lang, a German immigrant who had been living at St. Lucie to the north. Lang and Ivey were frustrated when Papy refused to turn off the light to handicap naval blockaders from the North. Lang found others who shared his cause—John Whitton, James E. Paine, and Paul Arnau—and they expelled Papy from his post, dismantled part of the lighting mechanism, and buried it. The lighthouse remained dark until 1866.

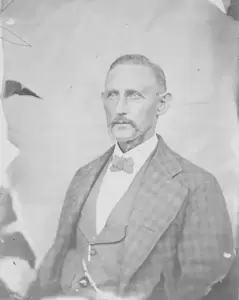

Captain James Arango Armour, a Confederate deserter, spent much of the war capturing Confederate blockade-runners. Armour helped to find the missing parts for the Jupiter light and delivered them to Key West for safekeeping. After the war he became assistant keeper at the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse, then head keeper in 1869. During the next 40 years, James Armour had many assistants who frequently became permanent settlers. Their positions allowed them a base from which to explore the area and accumulate funds until they chose a site to homestead.

For many years, the keepers, two assistants, and any family they had shared a 26-by-30-foot home with an outdoor kitchen. In 1883 the house was enlarged to two floors for the assistants, and a new keeper’s house was added; neither exists today.

Keepers of the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse - Pioneer Era

Thomas Twiner June 12, 1860 to January 1, 1861

Joseph Papy January 1, 1861 to August 15, 1861

Lighthouse deactivated August 15, 1861 to July 10, 1866

William B. Davis July 10,1866 to December 16, 1869

James A. Armour December 16, 1869 to September 15, 1906