U.S. Military in Boca Raton

By the time World War II began, both the U.S. Navy and the army’s Signal Corps had developed techniques for airborne radar (an acronym for radio detection and ranging). A radar post in the hills above Pearl Harbor spotted the Japanese attack in December 1941, but could not alert the main forces in time. The Army Signal Corps opened a radar school at Camp Murphy, now Jonathan Dickinson State Park in Martin County, and the Army Air Corps wanted a similar site close by. They considered Vero Beach, but after lobbying by Boca Raton’s mayor, Jonas C. “Joe” Mitchell, the Air Corps’ Radio School No. 2 opened (No. 1 was in Illinois) on land that would become the site of Florida Atlantic University and Boca Raton Airport.

About 50 owners of over 5,820 acres were forced to sell their land to the government under the Second War Purposes Act, including the Town of Boca Raton and the Lake Worth Drainage District. As explained in the Miami Herald on May 17, 1942, owners were notified “to vacate immediately all the land west of the railroad at Boca Raton. No financial offer has been made by the government to the owners of the land, but an appraisal is being made under the supervision of Lieutenant Colonel H. H. Cox.” Some people reportedly resisted being moved from their land, or felt officials treated them unfairly. In addition to legal owners, about 40 African-American families were removed who were squatters in the neighborhood of Fortieth Street.

William R. “Bill” Zern Jr., who started working with West Palm Beach mortician Mo Mizell in 1943, recalled in 2006: “There apparently had been a cemetery about where the field was, and Mo Mizell had been hired to move the bodies down to where Boca Raton Cemetery is now (449 SW Fourth Avenue).”

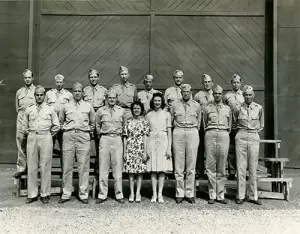

Boca Raton Army Air Field officially opened on October 12, 1942. The army constructed more than 800 buildings. Four runways were installed to train pilots on B-17s, and airplanes came from all over to have radar installed. Aviation cadets sometimes spent up to 20 hours per day on academic and military training. Classes included engineering, aerodynamics, and communications. After finishing their education at Yale University, these cadets were commissioned officers.

The Air Corps also took over the luxurious oceanfront Boca Raton Club to house trainees and officers from the radar training school. Residents reported conditions were anything but elegant, however. The expensive furnishings had been replaced by standard army bunks housing eight to a room, the swimming pool was boarded over, poor water pressure made bathing difficult, and a rigorous schedule allowed no excuses. When the club became too crowded, the grounds, including the golf course, turned into a tent camp.

African-American soldiers were segregated in Squadron F. Their housing, meals, training, and recreation were all separate from the white soldiers.

Although Boca Raton’s population was only 723 in 1940, during the war years it increased by 30,000 servicemen and women, civilian employees, and their families. Over 100,000 troops passed through Boca Raton for training or en route to service in the Pacific or Europe. The activity created a boom for the area, as Boca Raton residents alone could not fill all the needs of the military. In 1944 J. Myer Schine bought the Boca Raton Club and modernized it for a new life as the Boca Raton Hotel and Club. The Boca Raton Army Air Field operated until 1947.

Post-War Military Secrets

After World War II, the Boca Raton Army Air Field was shut down except for 838 acres known as Boca Raton Air Force Auxiliary Field, a backup for Morrison Field. From 1952 to 1957, during the Cold War with the Soviet Union, another 85.4 acres to the north were used for top-secret military activities. The Palm Beach Post made it public in 2001 after obtaining official documents and interviewing veterans and experts.

During the Cold War, the U.S. Government pursued the development of biological weapons for use in the event the Soviet Union initiated a biological war. The military spent about $8 million, in 1950s dollars, on a program designed to stop wheat production and force the Soviets to choose between surrender and feeding their civilian population. Boca Raton was one of many research sites scattered around the country, including Immokalee, Belle Glade, and Ft. Pierce in Florida. Boca Raton was chosen for its isolation, size, and climate.

The U.S. Chemical Corps recruited enlisted men from the farm states of the Midwest. Close to a hundred men worked from a large laboratory in a Quonset hut at the north end of the test site. No one wore uniforms, and vehicles were painted black. The men planted wheat between and along the runways of the former airfield, now the site of the Boca Raton Airport and Florida Atlantic University. When the wheat was about a foot high, it was sprayed with a fungus called “stem rust of rye,” which formed spores that multiplied rapidly. Every three days, the men vacuumed up the resulting millions of spores and packed them in one-to-two gallon stainless steel containers, which were driven to the Avon Park Bombing Range, near Sebring. From there they were flown to an unknown destination.

If biological warfare became necessary, the spores were to be dusted onto chicken feathers, then loaded into a container that would explode about 500 feet off the ground, spreading the feathers; the fungus spores would destroy the wheat crops in about 24 hours.

In 1957 the Chemical Corps shut down the secret operation at Boca Raton and kept only a skeleton crew at the base. Two years later, the military turned over the remaining property to the City of Boca Raton and the State of Florida. The wheat disease gathered from Boca Raton and related sites was destroyed in 1969 by order of President Nixon.

A 1994 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers survey found nothing harmful at the test site in Boca Raton. U.S. Senator Bill Nelson initiated a Senate investigation of the program after the Department of Defense refused his request for information.